The invisible rhythm that powers our modern world—electricity's frequency—is a marvel of engineering. Yet, what exactly goes into producing and maintaining that precise pulse, whether it's powering an entire city grid or crafting the subtle signals for your smartphone? Understanding How Frequency Generators Work: Internal Mechanics & Design reveals the hidden artistry behind stable power and advanced electronics.

From the massive engines that spin to keep your lights on, to the delicate circuits that create the intricate waveforms essential for communication, "frequency generator" is a broad term encompassing remarkable devices. Each is designed to deliver a specific oscillatory output, but their internal workings couldn't be more different.

At a Glance: What You'll Discover About Frequency Generators

- Dual Nature: The term "frequency generator" refers to both large power generators that maintain a stable grid frequency (e.g., 50/60 Hz) and electronic devices that produce specific frequencies and waveforms for testing and signal processing.

- Power Generators: Their frequency is directly tied to engine speed (RPM) and alternator poles, meticulously controlled by governors (for speed/fuel) and Automatic Voltage Regulators (AVRs, for voltage).

- Electronic Signal Generators: These use oscillators to create basic waveforms (sine, square, triangle), amplifiers to boost signals, and filters to refine them.

- Critical Importance: Stable frequency prevents equipment damage, ensures reliable communication, and is vital for everything from medical diagnostics to scientific research.

- Future: Expect greater software integration, miniaturization, and enhanced precision across both types of generators.

What Exactly Is a Frequency Generator? Unpacking the Term

Before we dive into the nuts and bolts, let's clear up a common ambiguity. The term "frequency generator" can refer to two fundamentally different, though equally vital, categories of devices:

- Grid-Scale Power Generators: These are the large diesel, gas, or turbine-driven systems that generate the bulk electricity supplied to homes and industries. Their primary job, beyond producing power, is to maintain a stable output frequency—typically 50 Hz or 60 Hz, depending on the region. This stability is paramount for the entire electrical grid.

- Electronic Signal Generators (Function Generators): These are precision electronic instruments that create specific oscillating electrical signals (waveforms) at user-defined frequencies. Engineers, technicians, and scientists use them to test circuits, calibrate equipment, and simulate various conditions in telecommunications, audio, and research.

While their purpose differs, both types of devices share a common goal: the accurate and stable generation of electrical frequency. Let's explore the distinct internal mechanics of each.

The Rhythmic Heartbeat of Power: How Grid-Scale Generators Maintain Frequency

Imagine the electrical grid as a vast, interconnected symphony. If one instrument goes off-key—or in this case, off-frequency—the whole performance suffers. For large power generators, maintaining a stable frequency is not just good practice; it's absolutely critical for preventing chaos.

In places like Australia, the standard is 50 Hz. This isn't just a number; it's a tight dance, typically needing to stay within a narrow band, say 49.5–50.5 Hz. Straying too far can lead to flickering lights, sensitive medical equipment malfunctioning, or industrial machinery grinding to a halt.

The Foundation: RPM, Poles, and the Hertz Equation

At the heart of a power generator's frequency output are two mechanical factors: the rotational speed of its engine (Revolutions Per Minute, or RPM) and the number of magnetic poles in its alternator. These are linked by a simple, yet powerful, formula:

Frequency (Hz) = (RPM × Number of Poles) ÷ 120

Let's break that down:

- RPM: This is how fast the generator's engine is spinning. The faster the engine, the more cycles of electricity can be produced per second.

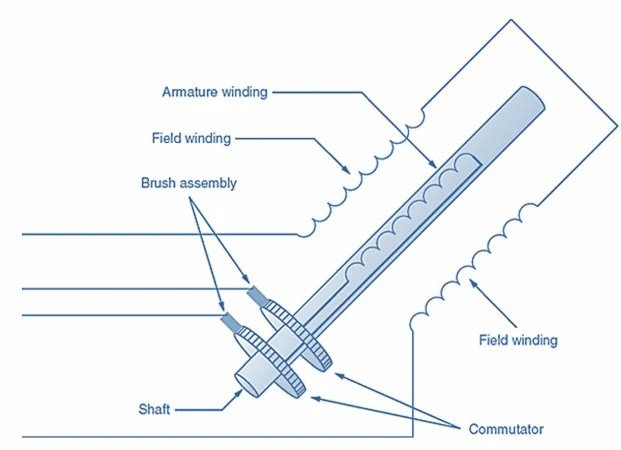

- Number of Poles: The alternator, which converts mechanical energy into electrical energy, contains sets of magnetic poles (north and south). Each pair of poles produces one complete cycle of AC electricity as the rotor spins past them.

Consider a common setup: a 4-pole generator spinning at 1500 RPM. Plugging those numbers into the formula: (1500 RPM × 4 Poles) ÷ 120 = 50 Hz. This configuration is widely used for 50 Hz systems because it balances efficiency, noise levels, and engine lifespan. To get 50 Hz from a 2-pole generator, the engine would need to scream along at 3000 RPM, often leading to more wear, noise, and fuel consumption.

Understanding these fundamentals is key to appreciating how these mechanical beasts keep our power supply rock-steady. Learn more about hz generators and the standards that govern their operation.

The Brains of the Operation: Governors and AVRs

While RPM and poles set the theoretical output, the actual maintenance of frequency in real-world conditions is the job of two unsung heroes: the governor and the Automatic Voltage Regulator (AVR).

The Governor: The Speed Master

Think of the governor as the generator's cruise control. Its primary task is to constantly monitor the generator's engine speed (and thus, frequency) and adjust the fuel supply to keep it consistent, even as the electrical load changes.

- Sensing Load Changes: When you switch on a powerful appliance like an air conditioner, it creates an immediate demand for more power, which temporarily "drags" down the generator's engine speed. The governor senses this dip.

- Adjusting Fuel: In response, the governor increases the fuel supply to the engine, boosting its power output to compensate for the added load and restore the target RPM and, by extension, the target frequency. When the load drops, it reduces fuel to prevent overspeeding.

Governors come in different flavors: - Mechanical Governors: These are older, often simpler systems that use flyweights and springs to sense speed changes. They are reliable but typically slower to react.

- Electronic Governors: Modern generators, especially advanced inverter generators, use electronic governors. These leverage sensors, microprocessors, and sophisticated algorithms for much sharper, faster, and more precise control over engine speed and fuel delivery. This precision is crucial for highly stable power, which is why inverter generators are often prized for sensitive electronics.

The Automatic Voltage Regulator (AVR): The Voltage Stabilizer

Working hand-in-glove with the governor is the AVR. While the governor handles speed and frequency, the AVR tackles voltage stability.

- Adjusting Field Current: The AVR constantly monitors the output voltage of the alternator. If the voltage starts to dip (perhaps due to increased load), the AVR increases the current flowing through the alternator's excitation field. This strengthens the magnetic field, which in turn boosts the output voltage back to the desired level. Conversely, if voltage rises too high, it reduces the field current.

Together, the governor and AVR form a dynamic duo, ensuring that both the frequency (the rhythm) and the voltage (the strength) of the electricity remain stable, protecting all connected devices.

Handling the Hiccups: Frequency Stability and Its Challenges

Even with sophisticated governors and AVRs, maintaining perfect frequency isn't always a given. Several factors can throw a wrench into the works:

- Sudden Load Changes: Large, abrupt increases or decreases in demand can overwhelm even the best control systems, causing momentary dips or surges in frequency.

- Fuel Supply Issues: A dirty fuel filter, an inconsistent fuel pump, or a low fuel level can starve the engine, hindering the governor's ability to maintain speed.

- Engine Health: Worn engine parts, clogged air filters, or poor maintenance can reduce the engine's responsiveness and overall power, making it harder to adapt to load changes.

- Control System Malfunctions: Issues with the governor or AVR themselves—faulty sensors, software glitches, or electrical failures—can directly lead to frequency instability.

Symptoms of Instability: You'll notice these problems: flickering lights, appliances buzzing or humming oddly, or sensitive electronics shutting off or resetting themselves.

The Fix: Regular maintenance, recalibration of governor settings, and software updates for electronic control systems are crucial. In high-demand or critical settings, dedicated external frequency regulators can provide an extra layer of precision and stability.

Crafting Custom Signals: How Electronic Frequency Generators Work

Stepping away from grid power, electronic frequency generators—often called function generators or signal generators—operate on entirely different principles, designed not to maintain a grid standard, but to create a vast range of specific signals for testing and development. These devices are the workhorses of electronics labs, telecommunication centers, and scientific research facilities.

More Than Just Power: Oscillating Signals on Demand

An electronic frequency generator produces an oscillating electrical signal of a specific frequency and waveform. Unlike a power generator that aims for a steady 50 or 60 Hz sine wave, these devices can output a spectrum of frequencies, from a few hertz up to many gigahertz, and a variety of waveforms:

- Sine Wave: A smooth, continuous oscillation, ideal for audio testing, radio frequency (RF) applications, and general analog circuit analysis.

- Square Wave: Characterized by sharp, instantaneous transitions between high and low voltage levels. Essential for digital circuit testing, clock signals, and pulse generation.

- Triangle Wave: Features a linear rise and fall, creating a symmetrical triangular shape. Useful for testing linear systems, voltage-controlled oscillators, and modulation.

- Sawtooth Wave: Similar to a triangle wave but with a slow linear rise and a rapid drop (or vice versa). Often used in sweep circuits, timing, and some audio synthesis.

- Pulse Wave: A square wave where the high and low duration can be independently controlled (pulse width modulation).

These custom signals are vital for simulating real-world conditions, diagnosing problems, and developing new technologies.

Inside the Signal Factory: Core Components

Electronic frequency generators, regardless of their complexity, rely on a few core components working in harmony to produce their precise outputs:

1. The Oscillator: The Signal's Genesis

This is the heart of any electronic frequency generator, responsible for creating the initial, fundamental oscillating electrical signal. Oscillators come in many forms, each suited for different applications and performance requirements:

- RC Oscillators (Resistor-Capacitor): Simpler, often used for lower frequencies, relying on the charging and discharging of capacitors through resistors to generate oscillations. Examples include Wien bridge oscillators for sine waves.

- LC Oscillators (Inductor-Capacitor): Utilized for higher frequencies, relying on the resonant properties of inductors and capacitors. Colpitts and Hartley oscillators are common types.

- Crystal Oscillators: Employ a piezoelectric crystal (often quartz) that vibrates at a very precise frequency when an electrical current is applied. These offer exceptionally high frequency stability and accuracy, making them ideal for reference clocks and stable signal generation.

- Voltage-Controlled Oscillators (VCOs): Their output frequency can be varied by an input voltage, making them crucial for frequency modulation (FM) and phase-locked loops (PLLs).

- Direct Digital Synthesis (DDS): A modern technique that uses digital signal processing to create very precise and stable waveforms. A digital accumulator generates phase values, which are then converted into an analog waveform by a Digital-to-Analog Converter (DAC). DDS generators offer excellent frequency resolution, fast switching, and low phase noise.

The accuracy and stability of the entire generator heavily depend on the quality and design of its oscillator. High-end units are engineered for extremely low phase noise (unwanted rapid fluctuations in phase) and high-frequency stability (how well the frequency remains constant over time and temperature).

2. The Amplifier: Boosting the Signal

The raw signal from the oscillator is often too weak for practical use. The amplifier stage boosts the amplitude (strength) of the signal to a usable output level, which can typically be adjusted by the user. This allows the signal generator to drive various loads, from small sensors to larger power circuits.

3. The Filter: Shaping the Sound

Filters play a crucial role in refining the generated waveform. Even a well-designed oscillator might produce harmonics (multiples of the fundamental frequency) or other unwanted noise. Filters remove these undesirable components, ensuring that the output signal is as clean and pure as intended. For example, a low-pass filter can make a square wave closer to a sine wave by removing its higher harmonics.

Why They Matter: Applications Across Industries

Electronic frequency generators are indispensable across an astonishing array of fields:

- Telecommunications: From designing antennae to testing cellular base stations, they generate the carrier signals, modulate data, and evaluate receiver sensitivity.

- Audio Equipment Development: Used to create precise sine waves for speaker testing, square waves for digital audio circuit debugging, and complex waveforms for analyzing amplifier distortion.

- Medical Devices: Crucial for diagnostic tools like ultrasound machines (generating specific ultrasonic frequencies) and various therapeutic applications.

- Scientific Research: Applied in fields such as spectroscopy (exciting samples with specific frequencies), material testing, and experiments requiring precise timing and frequency control.

- Education and Training: Essential tools for teaching electronics principles, signal processing, and laboratory experimentation in engineering schools worldwide.

Choosing Your Frequency Generator: Key Considerations

Whether you're an engineer, a hobbyist, or a technician, selecting the right frequency generator involves weighing several factors specific to your needs:

- Required Frequency Range: What minimum and maximum frequencies do you need to generate? This dictates the complexity and cost.

- Waveform Types: Do you primarily need sine waves, or do you require square, triangle, pulse, or arbitrary waveforms (user-defined custom shapes)?

- Output Amplitude and Impedance: What voltage levels do you need, and what kind of load will the generator be driving? Output impedance (typically 50 Ω) is also critical for RF applications.

- Stability and Accuracy: For precision work, look for specifications like low phase noise, high-frequency stability (often expressed in parts per million or ppb), and accurate amplitude control.

- Connectivity Options: Do you need USB, Ethernet, GPIB, or other interfaces for remote control and automation?

- Modulation Capabilities: Can it perform Amplitude Modulation (AM), Frequency Modulation (FM), Phase Modulation (PM), or Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) if needed for communication or signal processing?

- Budget and Portability: High-end lab equipment costs significantly more than a basic benchtop unit or a portable handheld generator.

The Future of Frequency Generation: Smarter, Smaller, More Precise

The evolution of frequency generators continues at a rapid pace, driven by demand for greater precision, flexibility, and integration.

- Greater Software Integration & Automation: Modern generators increasingly integrate with software environments (like LabVIEW or Python) for complex test sequences, automated calibration, and remote control, making them part of larger automated test systems.

- Miniaturization for Portable Applications: The drive towards smaller, more powerful electronics means more highly capable handheld and portable frequency generators, ideal for field service or educational kits.

- Increased Precision and Stability: For cutting-edge research and demanding applications like quantum computing or advanced radar, the quest for even lower phase noise, higher frequency stability, and broader frequency ranges continues.

- Smart Features and IoT Connectivity: Expect more generators with built-in intelligence, self-calibration features, and the ability to connect to the Internet of Things (IoT) for remote monitoring, diagnostics, and data logging.

These advancements will further expand the capabilities and applications of frequency generators, making them even more integral to future technological innovation.

Common Questions About Frequency Generators

What's the difference between frequency and voltage regulation in power generators?

Frequency regulation primarily controls the speed of the generator's engine, which directly determines the Hz output. It's handled by the governor adjusting fuel supply. Voltage regulation, on the other hand, controls the strength of the electrical output (volts) by adjusting the alternator's magnetic field, handled by the AVR. Both are crucial for stable, usable power.

Can I use a 50Hz generator in a 60Hz region, or vice-versa?

Technically, a generator designed for one frequency can often produce the other by adjusting RPM, but this is rarely recommended without specific design for it. Appliances are designed for their region's specific frequency. Using a 50Hz generator for 60Hz devices (or vice-versa) can lead to motors running too fast/slow, overheating, damage, or improper operation of sensitive electronics. It's always best to match the generator's output frequency to the equipment's rated frequency.

How often should a generator's frequency be checked or calibrated?

For critical applications or commercial generators, frequency (and voltage) should be regularly monitored as part of a routine maintenance schedule, often weekly or monthly. Annual or semi-annual recalibration by a qualified technician is highly recommended, especially for electronic governors and AVRs, to ensure sustained accuracy and prevent long-term performance drift.

Keeping the Beat: Final Thoughts on Reliability & Innovation

From ensuring the stability of our power grids to meticulously crafting the signals that underpin global communications, frequency generators—in their diverse forms—are true workhorses of the modern world. Their internal mechanics, whether mechanical-electrical marvels or precision electronic circuits, are a testament to human ingenuity.

Understanding these systems isn't just about technical curiosity; it's about appreciating the foundational elements that enable our electrically driven lives. As technology progresses, the demand for even more precise, stable, and versatile frequency generation will only grow, pushing the boundaries of what these essential devices can achieve. Staying on top of regular maintenance for power generators or choosing the right signal generator for your electronic needs means ensuring that the "beat" of your operations stays perfectly in time.